Critical technology development in the US is riding high, but that doesn’t come without challenges. Selling to the government is no easy feat.

Tommy Hendrix founded Decisive Point in 2018 to help solve that problem by making strategic investments into defense, energy, and infrastructure startups building critical tech. The firm helps startups navigate regulatory pathways and government contracting to gain access to their target markets. In the nuclear space, Decisive Point has invested in Radiant.

Recently, Hendrix has taken on a new challenge within the nuclear energy industry: the fuel problem. Through Standard Nuclear, which emerged from stealth last month with a Decisive Point-led $42M round of funding, Hendrix is looking to solve the fuel availability problem for the highly anticipated fleet of advanced nuclear reactors coming in the next few years.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ignition: Coming from your military background, what did your path look like to get to investing in critical infrastructure and critical technologies and then, by extension, to the nuclear sector?

Hendrix: I graduated from West Point in 2006, joined the Army, and we were the surge class. So pretty much everyone I graduated with went to Iraq for 15 months after their initial training. And I spent my time in the Army primarily within the Special Forces. I was a Green Beret. I served in a counterterrorism unit that was focused on everything from evacuating embassies to the initial push back into Iraq in 2014 when ISIS came in. And so it wasn’t standard. A lot of times, we were having to figure out the logistics for deploying forward with little or no US support, with everything that we could carry on a couple aircraft, including our helicopters, our equipment, our surgical teams. I really had a very fortunate career in the military—I never held a job that was not an operational command position, with the exception of the times I was in training.

When my time to transition to that part of my military career came, I got out. I left at 10 years, which is actually a pretty unusual time to leave. You’re halfway to retirement. When I came back to New York, a lot of my friends had transitioned into finance. They had a pretty good network there to start, and that’s where I made my entry point. I ended up going to business school at Columbia, and then was fortunate enough to get offered a job at Blackstone, and that was my first foray into the investment world. So while I was there, working in a strategy role, there weren’t that many veterans on Wall Street. I would often get pulled into discussions around some of their traditional aerospace investments just because I had been in the military, and what I saw was, even though the folks that were there were extremely experienced, successful investors, they didn’t actually understand how the government worked. They had consultants. They had former generals. And if you’re in the military, what you know about generals is that even though they have a tremendous amount of perspective and experience, they’ve been out of the tactical fight for a long time. And so one of the things that I started really thinking about while I was at Blackstone was this idea of investing in companies, but taking that more practical, ground level experience and injecting it into the companies that wanted to work with the government.

I left Blackstone, I started working with some companies, and what I learned very quickly in that process was that it wasn’t the fact that these companies couldn’t raise money or they didn’t know how to find things they were interested in within the government. It’s that navigating the complexities of the acquisitions process, the regulatory process was really difficult. That was the core for starting Decisive Point.

How do you assess the quality of a new startup in defense tech, critical tech, or energy, and its ability to access those regulatory pathways?

When we look at companies, I generally bucket them in three ways. The most important thing for us when we’re looking at a deal is, can we actually help this company? And the truth is that there’s a lot of great ideas out there, but if programmatically there’s not the mandate from the government to solve the problem that the company’s solving, and there’s not the budget that exists within the government appropriate from Congress to solve that, then it’s much harder to navigate the process.

The first category is the government is either their first or primary customer. So that captures a lot of pure defense, that captures a lot of the types of things where either to get off the ground, they need to gain some traction within the government, or they want to sell directly to the government, and that’s going to be their largest customer base.

The second is technology is where the commercial market might be nascent today, but the government continues to pour a lot of R&D funding into those areas, because strategically, the government believes they’re going to be really important in the long term. These are things where even, for some of the bleeding edge technology areas, that maybe there has not been a fully built-out commercial use case, but where the government continues to fund those things.

And then the third, which I think largely nuclear falls into, is companies where their biggest market is the consumer market or the commercial market, but there is a regulatory reason that they must win in government first. So if you think about a nuclear company, they must navigate licensing, they must navigate the regulatory environment first before they ever reach commercial success.

For us, it’s much more about where they fit in the framework of us being able to actually help them, and us being able to give them some sort of asymmetric advantage, compared to just trying to hack through the bureaucracy themselves. And in some cases, it’s much less about disruption and much more about process.

How do you weigh the costs and benefits of investing in a startup that faces a difficult regulatory pathway, like a nuclear company?

I think for a lot of people, they look at the regulatory environment and they think of it purely as a hurdle, right? And it is a challenge, but it also creates an incredible moat to a lot of businesses, and a lot of big businesses have been built inside that moat. So the way that we think about it, and what we often tell startups, is if you’re out there constantly railing against the process or saying how much the process needs to change, the productive way to approach it is to navigate the process as it currently exists, push to the limit on speed, and then once you hit those walls, that’s where you can start to try and enact change.

You can’t just be a company that submits a lot of proposals and doesn’t get involved in the rest of the process and expect that to work. You also can’t be a company that tries to be a lobbyist and just lobby for your revenue. So the answer is, you have to be doing a lot at once. It’s a complex market, but if you have the patience for some of these highly capital-intensive, long-duration investments, this should just be another piece of what you have to navigate to make those companies successful.

What made Radiant stand out to you as a valuable investment?

We invested in Radiant’s Series A. It was early days, no reactor, no equipment, just a bunch of folks—I think there were five people at the time—with desks and computers, and they had just moved into their first proper space. The things that were attractive were the founding team, specifically Doug and Bob had come from SpaceX and had worked on pretty hairy problems there, and they understood that the regulatory environment was really where they would win.

I reached out to Doug, and I said, “here’s what we do. We help companies with government contracting, and we deal with the government.” I think his response to me was something like, “That’s exactly what we’ll need in the early days.” And we, you know, when we invest in a company, you get, you know, two or three people basically tacked on to your business to deal with the government. And so it’s a huge benefit.

But we just saw the opportunity to look at a company that was addressing a problem which the government, at that point, had already said that they were interested in investing in. If it was four years earlier, pre- some of the programs that the government had rolled out, it would have been probably too risky or too far out for us, but we try and map very closely to where the federal budget is going.

It’s not too controversial to say that the US is pretty bad at producing uranium fuel right now. Why is that, and how did we get here?

It’s this combination of public perception and political inaction that drove down our willingness to invest in nuclear. But the industry is at fault too, right? It’s, I mean, it’s an industry that is built for pain when you look at the supply chain. None of the companies are in adjacent pieces of the fuel supply chain process. None of the companies that are doing enrichment are also doing conversion, or, for the most part, also doing deconversion. There’s an extremely inefficient supply chain that exists already for an extremely complicated, heavily regulated industry.

The truth is, in the nuclear space, it seems that tech does require a bit of gray hair before people are comfortable with it, and so I think that’s just kind of where we are in an evolution of bringing some of these new technologies online. No one’s really proposing some radical new technology. They’re new designs, they’re new ways of approaching old problems, but for the most part, it’s a lot of well tried and true technology, because we’ve already demonstrated that works at some point in the past.

I think it’s probably this perfect storm of negative public perception. Certainly, there’s been a massive lobbying effort to ensure that this is not the power of choice. And so that’s where we end up, where we’ve really sat on our heels and let other countries take a lead position here. And I think it’s probably less about nuclear specifically, and more the story of, our entire industrial might for the last 40 years.

Tell me the brief founding story of how Standard Nuclear came to be.

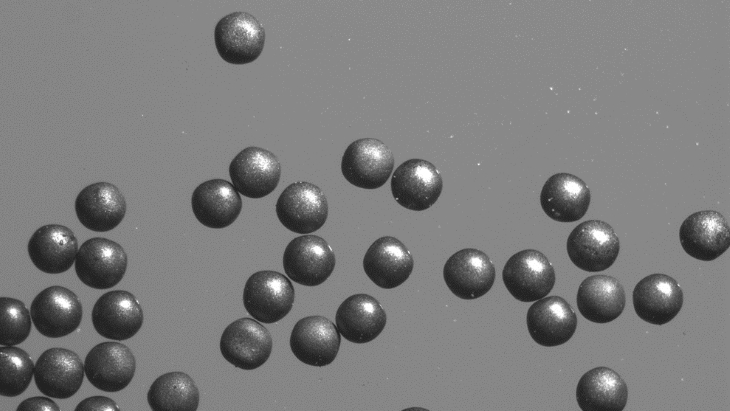

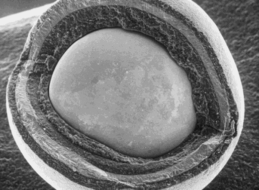

We, of course, invested in Radiant, but we were believers, and we have been for a long time, that lots of these reactors are going to turn on. And along the way, we’ve looked at the fuel choice for a lot of these reactors. And if you look at the reactors and pre-licensing, the vast majority of them are using TRISO.

For the three or four years now that we’ve been invested in the space, there’s been an assumption along the way that the fuel was going to materialize, it was going to be there by the time the reactors were ready, and it was a question that the reactor developers were constantly getting asked. A lot of the response was, “Well, it’s going to come from this one vendor which is largely servicing the government, or the labs are going to contract for it.” It’s not going to necessarily be their problem to solve. And it was about 18 months ago when I think we kind of hit the point where we no longer believe that to be true.

Not only did we not believe it to be true, in that it just didn’t seem like the capacity was going to be there. It was the notion that as this race got more and more competitive, as more reactors were getting to the point where it was clear they weren’t going to meet their timelines for demonstration, we began to ask the question constantly of, “Why would this reactor company, which is vertically integrating to make their own fuel—why would they sell you fuel to help you demonstrate before them, what would their incentive be?” What would the incentive be for you to be the first reaction to turn on instead of them? And if they have the fuel and they can hold it over you, why wouldn’t they? And again, that’s not a criticism of one specific company. It was across the entire landscape.

Following a couple discussions, we decided that we were going to incubate a fuel company. And the logic was not that we were going to sprint ahead of competition. We knew the licensing process was a long, long process, five to seven years, and if we didn’t start it today, it wasn’t going to be there.

The only way, if you just look at every other commodity market, the only way that you get to those sorts of lower prices is by effectively increasing the volume and decreasing the cost, pushing towards standardization, all these things that we’ve seen in oil, natural gas, they still need to happen in any other competitive commodity market, and we didn’t have that. So we went down that path.

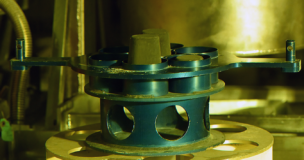

Ultra Safe Nuclear had built their own commercial, private facility, which was an industrial scale line. And I also was talking about getting told consistently that, you know, if I could somehow lure away Kurt Terrani from Ultra Safe Nuclear, he was the guy who had built the line and had the vision and was really an expert in the space. And so as we were going through this process, a couple months into it, I got a phone call from one of the larger nuclear companies saying, “Hey, this is a bit outside of scope for us, but we’ve heard about what you’re doing. It seems credible. And you know, we’ve been told Ultra Safe Nuclear is going to go into bankruptcy. Would you like to get involved?” And that’s where we started this process.

At this point, you’ve invented in a microreactor company, and now in uranium fuel. Are there any other areas in the nuclear fission or fusion sectors that you are interested in investing in?

We’ve looked at a lot of fusion companies, and it’s really interesting. I think it’s still probably too far out from a power generation standpoint for us.

I think that fuel reprocessing continues to be really interesting. I think that there’s other applications of nuclear technologies, and we’re seeing that in like, you know, radio isotope battery type applications. They’re all going to have a place. And I think this ends up being a bit like an all of the above strategy. It really is a once in a generation opportunity right now where the government has the intense willingness to cut regulation. And I think if you’re able to put good ideas in front of the government right now, in front of regulators, the government has signaled that they’re willing and interested for this to become a part of our energy solution in both parties. This is an extremely, extremely rare thing that happens within US politics. So the time is now to jump on those sorts of things.

Lead Reporter of Ignition