A word to the nuclear energy industry: you’re not that special.

Michael Crabb, SVP of commercial at Last Energy, has spent his career working in energy investment and financing. For him, when it comes down to it, all the groundbreaking technology in the world don’t mean a thing if it doesn’t fill a need and compete on price.

Now, Crabb is working on the commercial approach for Last Energy, a US startup developing scaled-down nuclear reactors for industrial projects. Ignition talked with Crabb to discuss nuclear’s place in the energy sector, creating energy abundance, and where the need is for new power sources.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ignition: What was your path into the nuclear energy sector?

Crabb: I started in the energy space fresh out of undergrad. I was able to join a private equity firm that focused on energy investments where we specialized in power, power plants and natural gas and midstream infrastructure. Two funds, and at our largest we had $7.5B of assets under management. And it was just a great introduction to the entire energy industry.

The first five, six years of my career, we ended up basketing a portfolio of gas-fired assets and sold them to some other private equity funds. And at that point, I was like, What is this? This is sort of silly, right? We’re just trading around power plants. And it created a lot of value, but it was all financial.

Then I spent a couple of years doing liquefied natural gas development for small scale industrial applications…until my first bout with commodity prices. The oil market went from $110 to $30 and just wiped away our economic value proposition.

There’s two key lessons. One is that price is everything. Everyone can say what they want about decarbonization, but price drives all decisions. The second is commodity prices are fickle. You can’t count on them. Anyone in the energy space has learned by being on the wrong end of that.

I had a first call with Bret [Kugelmass], our founder here at Last Energy, and he just said a lot of things that clicked. He came at it from a first principles approach. He had no energy background, but arrived at a very similar place where I had, with all energy background…That, combined with the opportunity to leverage my skill set to build the business, was really exciting and attractive. And so I actually took the job.

When you first joined Last Energy, what was it about the business that you connected with?

I think it was the opportunity to have something that would so materially impact how we create abundance in human society. I never considered myself a super mission oriented person. I always thought that was a little bit of liberalism, a little bit cagey, a thing people say to make them feel better about solar projects and like the tax equity that mostly goes to the big banks.

We’re doing a lot of stuff, and it’s fun to kind of sit back at the end of the day and know that we’re doing it in a way that could really materially change how we function as humans.

What do you think are the major pitfalls that SMR developers run into as they build a business model for their technology?

The number one rule in venture investing and building a business, whether it’s a laundromat or a SaaS company or a nuclear company, is you fall in love with the customer problem, not the solution. When we’re doing gas midstream pipelines, you want a demand pull and not a supply push. You can’t just build a pipeline and hope people will start drilling on one end and consuming hydrocarbons on the other.

What is the economic problem that Last Energy is aiming to solve for its customers down the line?

It’s electricity consumption for industrial customers. The energy market is actually incredibly diverse. Even just in the United States, we have eight or 10 different market regions for electricity. You don’t have to just sell a product to a utility. Most of these markets have been deregulated, meaning anybody can go out and build and develop a power plant and bring the contracts together to execute on that power plan. It’s sort of a form of real estate development.

We’re able to identify a niche of industrial customers that have a baseload demand for power, and we sell them power at a fixed price that can be 20, 30, sometimes 40% cheaper than their alternative of buying power from the grid.

I think it’s also kind of a timely conversation, given that AWS just announced this acquisition of a data center that’s hooked up directly to a nuclear plant. I’m curious just to hear your thoughts on that partnership, and what that means for your business.

It’s fantastic. The data center space in particular has a whole bunch of limitations around growth related directly to energy. It’s great to see that Microsoft hired a whole nuclear team. It’s great to see Amazon jump in. All the hyperscalers are looking at a whole long list of ways to supply their energy demands, nuclear and non-nuclear.

What is Last Energy’s technological approach, and how is it different from other players in the market?

We don’t approach it that way. We don’t say it’s a technological problem. The real problem is one of schedule, right? A customer like Amazon needs power. They’re building data centers. They don’t need it in 2035, they need it right now, and if you could get it yesterday, they would.

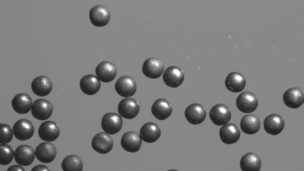

The one thing that the industry does really well is the technology. We don’t invent new technology. We do units smaller.

Where are you focusing your efforts to sell this product to customers, and in those markets, what are you up against?

We have a set of target markets in Europe. They all have slightly different flavors. Some have higher energy prices, but more bureaucratic development, longer process timelines. Others have a little more political instability. Each project has all these little nuances to it, and that’s the fun of energy.

We’re somewhere in the mid-development phase with 10 or 11 projects. We’ve gotten a bunch of others in the top of that funnel that span from steel manufacturing to data centers. It’s a really nice diversification with different end-use customers and discrete economic problems that we’re solving…That diversification is critical, right? It’s the same strategy that any other real estate developer and certainly energy real estate developer takes.

What you didn’t hear me say is just as important as what I did say, right, which is this, “Oh, people are against nuclear. It’s really hard. Everyone opposes it.” The data just doesn’t show that, and the activity on the ground doesn’t show that either. Everyone just sort of opposes everything all the time. For the most part, people hear nuclear and they’re like, “Oh, it’s only this small of a footprint? It’s only this small of a building? You only have this many trucks? That’s fantastic.”

What do you think are the hallmarks of a successful nuclear energy company?

I don’t think we’ve seen a successful nuclear company. If our goal is to build out nuclear at scale to effectively save humanity, we haven’t seen that yet. What I think would be the hallmarks of a successful nuclear industry is a robust set of market projects. We can end up with 10 or 20 or 40 successful nuclear companies if we can create a robust marketplace of projects, and move away from the government picking winners and writing blank checks.

What new regulation or dropping of an old regulation would help your business the most if it passed today?

I think it’s applying frameworks that are used across energy projects instead of creating discrete processes for nuclear. There’s a bunch of redundant legislation and additional paperwork, things that have zero real benefit in different geographies, that are just human interventions. Frankly, it’s totally unnecessary.

Lead Reporter of Ignition