Commercial fusion isn’t going to suddenly come into existence through the sheer power of imagination and passion. It’s going to take a lot of nose-to-the-grindstone work in the shop, not to mention world-class engineering chops and ingenuity, to finally make theory reality.

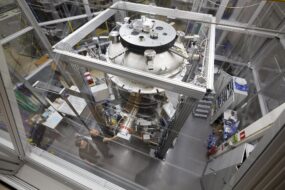

It’s that first-principles emphasis that Brian Riordan, cofounder and COO of commercial fusion startup Avalanche Energy, has adopted as the company’s driving approach. Avalanche is working to build Orbitron, a fusion microreactor free of high-powered magnets or lasers, meant to be easily manufacturable and transportable.

Ignition caught up with Riordan to talk about the company’s approach to the monumental challenge of building commercial fusion.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ignition: Everyone’s got a different story. What did your path into fusion look like?

Riordan: My path is kind of pinball. I’m very interested in new problems, but I got into the workforce a little bit later. I had a bachelor’s in engineering but I always wanted to work on new problems, R&D, and something that other people didn’t want to touch because they’re not even sure it can be successful, or it’s too intimidating, or they don’t get to leverage their explicit training.

I bounced around from oil and gas to subsea mining, consumer products to aerospace. In aerospace [at Blue Origin], I was fortunate to be on a team that was well funded, and had a blank slate. And so I was able to go through the phases of extreme intimidation. I’m like, “How am I going to do this? I don’t know how to do this.”

I realized that if I got the right people and I got them communicating in the right interfaces, that you can break down problems—either by utilizing people with deep expertise in a subject matter or by getting the right team of people that are open-minded with strong fundamentals to bridge those gaps. It was really, really cool to see a team from disparate backgrounds be able to do something totally new.

I was able to work with Robin, my cofounder now, on some of those things in the very early days. And we had to present these things to Jeff Bezos, which was a little nerve-wracking in the beginning. We started talking about company culture, motivations, and retention, what really matters to a company, what matters to me as an individual who wants to grow and learn and feel secure and have fun and live out an engineer or scientist dream of building something new. And then we started talking about fusion.

The missing thing we saw for fusion reactors is that the problems in aerospace were related to the tools to be able to do the job, the hardware that you’re making, and the supply chain that supports it. And we found that there were step changes in designs largely focused on scale.

What changed in the tech and investment culture that made the time ripe to start Avalanche?

There were a lot of unturned stones and ways of getting to an architecture that could be net energy positive. Seeing new tools in everything from cloud computing to superconducting magnets to access to physics codes. You can simulate things before you actually build the hardware and test it and, we were getting more faith that there are tools out there now that weren’t available to people before. And we were seeing this confluence of those things.

At the same time, there was this move towards impact investment or climate investment and people were like, “I don’t want to really spend my money on another app where the whole business model revolves around turning a profit or being able to exit in two years. I’m willing to take a bigger bite of something that’s hardware focused.”

I think Tesla and SpaceX have a big credit there. Where there’s huge value and really hard tech, both the difficulty and the fact that there’s hardware gave both investors and potential employees for those kinds of companies a lot of inspiration and excitement. Like, “this is what I want to do. It’s fun, it’s going to change the world for the better.”

In transitioning into a commercially viable, smaller fusion reactor, what are the engineering challenges that you have to consider going into that shrinking down?

First, I would say that I think that’s a typical path for a lot of developments. We’re going to start this thing off big and then we’re going to shrink it. For fusion, I’d be a little cautious in talking about that roadmap, because the history of fusion has been that most designs require reactors so large that they want to prove the device at a smaller scale. The problem has been the physics have not scaled the way that the industry thought.

We said we want all the benefits for fast iterations for fusion, and to be able to do that we believe it has to be small for economics later on. Cars or phones or whatever, you’re not having one person sit down and build that. You have a manufacturing plant that has an assembly line manufacturing. If you want the economics to work for fusion, it’ll be like any hard tech you’ve seen that’s gotten cheaper and cheaper. That’s what we want to get out of this, and you’re not going to get it out of something big.

We’re this oddball not doing classic thermonuclear fusion. So how do we package it into something economical? We’re not there yet. Our roadmap is primarily burning down risks on the plasma physics itself, which is really tough, but there are some small things coming along.

There’s some work we do to bring down the uncertainty and show that you can take some of these things that have historically existed in a very large form factor and show that we’re able to get to the parameters we need to in something very small, both for capabilities and applications.

When you talk about burning down the risk to sufficient thresholds, what’s the goal? When you get to that threshold of sufficiently low risk, what then happens? Is it access to capital, is it building a market…what does that look like at that point?

Right now, burning down risk can increase credibility, it gives you access to regulators, it gives you access to DOE, DoD, different labs, different people with non-dilutive funding or grants that want to quantify level of uncertainty or technology readiness level. It’s really hard to know what your audience wants, and it’s all subjective. It’s the same thing for venture capital too, which is just overall more risk-tolerant. They have to be. If they don’t take risks, they don’t get invested in anything at a time that’s gonna give them any sense of growth.

There are some government grants out there, but unfortunately, how the government operates. It’s just never quite clear when that money will show up. We’ve got one right now where they thought they had the budget, and then they didn’t, and then they split the contract in half. And it’s like, I can’t run a company on these things. Working with VCs is the most sure way.

But you’ve got to educate, “Here’s our device, here’s how it works. We believe it’s going to work. Here are the milestones, and the level of uncertainty that we think it’s going to be, and here’s a critical one, and that’s why we think that’s a step change in company risk.” I tell the team what we’re doing is primarily selling a compelling story to investors. That’s what a risk burn-down gives us. That step. And then everybody buys into that, you get revalued, and then you start over again with the next major step.

Remind me how much Avalanche has raised in venture capital to date?

Just over $45M.

Taking a step back, broadly speaking, what is the use of a micro fusion generator?

It is kind of a new thing, but it’s also kind of an old thing. It generates electricity.

Everybody’s gonna need energy. And people are gonna want mobile energy. And if I get to have the benefits of saying that I don’t have this limited range, or I don’t have to haul around X tons of water, fuel or oil, I only have to haul around this way lighter thing, I then get to forget about all the logistics, or concerns that I can only go so far. I don’t have to make sure I have this much fuel, and this much extra in case there’s a storm, and then get in line to fuel, and fuel prices change, and I have to make sure my business plan handles that. It’s like, no, you’ve got energy security and that is going to last a very long time.

Lead Reporter of Ignition