The world needs more energy—we think we can all agree on that. That new energy ought to be clean, firm, and abundant. The fusion industry is rising to meet that challenge.

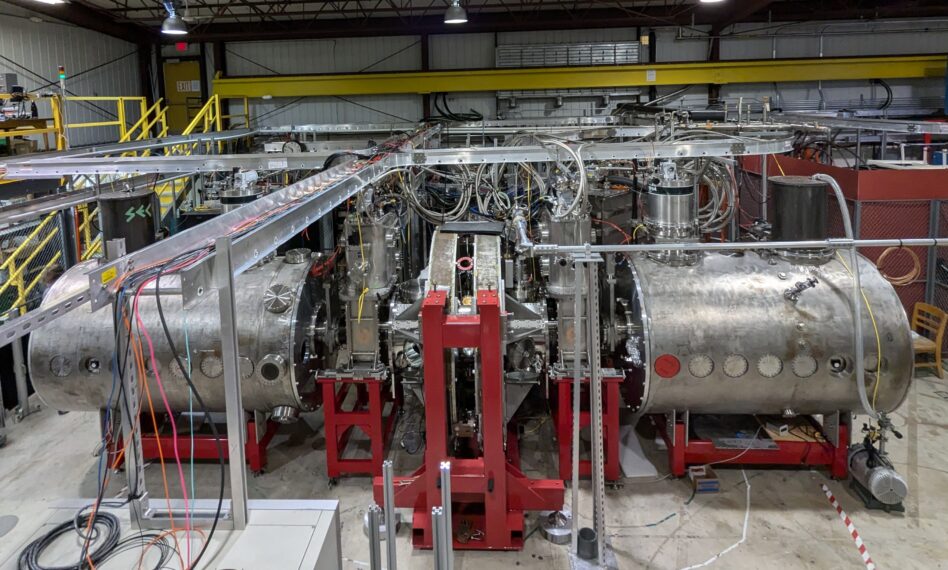

Realta Fusion is tackling the problem via the magnetic mirror approach, which—like many fusion concepts—was explored back in the ‘70s before falling off the funding priority list in the ‘80s. It’s back with a vengeance in Wisconsin, where the company is currently operating the WHAM experiment, using Commonwealth Fusion Systems-built superconducting magnets to fire plasma.

Ignition sat down with Realta CEO Kieran Furlong to talk about the company’s approach to fusion, the macro environment driving the need for new energy production, and what an eventual market for fusion might look like.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ignition: Tell me about the beginning of your interest in fusion energy. Where did it all begin for you?

Furlong: From an early age I was leaning in on environmental causes and just ensuring that we can keep the earth in a situation that is habitable for us humans. The Earth will continue on with or without us, but hopefully with us, and hopefully in an environment that is conducive to good quality of life, production of food, clean water, all of those things. So early on in my career, I focused on climate change being the big threat facing the future of humanity.

Spent the first decade of my career in the chemical industry, but was always gravitating towards renewable technologies, what we call climate tech nowadays. Went back to grad school and led the clean tech group at my grad school in Stanford and got plugged into the startup scene. This is in time for the first clean tech boom, and I had the advantage of actually having worked on some of these technologies in industry previously. So I looked at next-generation renewables, things like wave and tidal and so on, beyond wind and solar, ultimately ended up going down the biofuel route and worked in biofuels and bio-based materials. Hadn’t really looked at nuclear fission, because, I figured, I come from a nuclear free country. Fission just had lost its social license in so many parts of the world that I didn’t see that being a path forward for the future.

[At the University of Wisconsin] I first met one of my cofounders, Professor Cary Forest, and started talking about fusion. Initially I was somewhat skeptical, given the rapid growth that we’re seeing in wind and solar, whether or not fusion would be needed. The more I dug into it, the more I looked at NIMBYism and other factors on wind and solar, I recognized we really do need another abundant source of energy. Nuclear fission, for a variety of reasons, can play a role, but it’s not going to be the role that really fills that gap for 10 billion people. But fusion has the potential to do so.

You talk about this kind of social license that fission has lost, and this NIMBYism with wind and solar. What have you seen that makes you think that fusion is going to be different, that people are going to be happy to have fusion in their backyards?

Energy absolutely has to be an all-of-the-above solution. Right now, we probably only have the energy needs fulfilled for 2 billion people on Earth at the standard that we enjoy here in the developed world. We still have a lot more people who are deprived of abundant energy, and we’re going to have more.

Wind and solar, by necessity, require large areas of land or ocean.That’s one of the retarding factors—the places where people are not going to object to it are generally far away from people. And for a lot of things we do, we need energy near the sources, near the population centers. So that’s one of the challenges. Nuclear fission has been demonstrated to be the safest way to produce electricity so far in terms of the overall damage done to the environment and to people, but partly due to massive disasters like Chernobyl and so on—but also, I think, to the ongoing disconnect between how scientists and engineers think and talk to the public and what the general public likes to hear—it really has gone down the path of trying to reassure an emotional fear with additional engineering safety controls and so on, which has added cost upon cost, and now it’s getting to the point where it’s very hard to make economic justification for things like nuclear fission, the way it currently is designed, built and operated.

With fusion we have an opportunity to start a new conversation with the public and with communities, and we’re doing that already as a fusion industry. We’re trying to have that conversation from the very start, to make sure that we’re bringing people along with us to understand this is a different way of tapping into the massive amount of energy that’s possible in the atomic nuclei, and, you know, time will tell if we can get people on board. But I think there’s definitely strong prevailing winds with the huge need for energy for all aspects of human activity.

Even in the last two years, the amount of interest in energy for data processing has become huge. And this isn’t just because of the AI boom. I mean, it became a huge surprise to everyone a few years back when they realized 1% of global electricity was being used to mine cryptocurrencies. So like, we’ll find new uses for energy, and it all comes down to whether we produce enough of it at an economic rate that we can then continue to advance human development.

You’ve spoken before about fusion for data centers and for AI. Is fusion, or Realta’s approach to fusion, particularly well suited to meet the specific needs of data centers, or is this an issue of needing to grow global energy capacity in general?

I think it could be both. But there’s a very good combination of data centers with what fusion could potentially do.

Take Singapore for example. Singapore is one of the countries that, I think, will be one of the earliest adopters of fusion energy. There’s a country that has rapidly developed and is now a very wealthy country. 7% or so of its electricity currently goes to data centers. Singapore does not have sufficient surface area for solar. You’re not going to put offshore wind in the busiest shipping channels and on the planet, and the island, the country itself, is too small for the conventional exclusion zone that you’d have around a nuclear fission plant. So really, they’ve got very limited options if they want to have a secure supply of energy. Right now they rely on import from neighboring countries. That’s always at risk. If there’s a diplomatic spat, someone can turn off the tap. Fusion could definitely play a role there.

For data centers, they’re getting to a scale where more and more jurisdictions will start saying to the big tech companies, “Okay, you can build a data center, but you need to bring your power with you.” And that’s an area where, if you have a firm, always-on source of energy that can be built on a reasonable area of land right next to the data center, that’s going to be a positive.

What is the approach Realta is taking to fusion development, and why are you pursuing that approach?

What we’re pursuing is the magnetic mirror. Essentially this was the leading concept in US-based fusion research up until around the 70s, and in fact, the largest experiment ever constructed at Lawrence Livermore National Lab up until the 1980s was a magnetic mirror experiment. Unfortunately, that one never started up because fusion funding was cut drastically in the 1980s and that particular experiment was shut down. So the mirror was kind of put on the shelf here in the US, but research continued in other places, like Russia and Japan.

Our magnetic mirror you can think of as a plasma pipe. So it’s a linear system. It’s a cylinder. So my chemical engineering brain looks at the cylinder and says, okay, I can see engineering advantages and how to build and operate this. Back in the 70s and 80s, they recognized that if we can figure the physics out of this, the engineering is going to be easier, and that’s what we’re taking advantage of. We’re taking new learnings and we’re marrying them up with major advances made on high temperature superconducting magnets. We’ve basically got much stronger magnetic fields now that we can apply to the magnetic mirror.

One of the advantages is its scale, right? We have this linear device, which we can start small and then scale up in one direction. We can essentially make that cylinder longer and longer and longer. That offers some real tactical business advantages. One of the challenges when I first got involved in fusion was looking at many of the concepts out there. They really are kind of classic big science approaches. They require large amounts of capital, massive pieces of kit, demonstrated by the ITER experiment. And we recognized from the start we have to have something that’s the right size for private industry.

You’ve raised $16M for Realta so far and you’re aiming to keep the budget small. What is it about the company’s development process that allows you to keep costs comparatively low?

We spun the company out of a large ARPA-E funded project at the University of Wisconsin called the WHAM, and we are now sponsoring the research on that experiment. So it’s working both ways, but that enabled us to really leapfrog ahead of many other fusion companies out there. We have an operating fusion experiment. We’re firing plasma shots every day, gathering the data from those and using that to advance the technology. We are still going to need to raise significant amounts of capital for scaling up fusion machines and ultimately getting to our first fusion power plant. But we do think they’re going to be about an order of magnitude lower than some of the other concepts out there.

What have been some of the lessons learned from the plasma experiment?

One of the big things is just the fact that it turned on at all. That ticked so many boxes. At the start of this, one of the big question marks was, okay, there are new high temperature superconducting materials, but can strong enough magnets for this concept be built? Commonwealth Fusion Systems is a partner in that project, and they designed and manufactured the magnets for the project, which were delivered in July of last year. They turned on, we managed to strike a plasma, and that was at 17 Tesla, which was a world record for the magnetic field strength applied to a fusion experiment. So it was a huge step forward—the fact that such strong magnets could actually be manufactured, first of all, then that they could turn on and that they would stay on. Very first day of operation, we were able to strike a plasma, and we’re advancing now in terms of how we control that and stabilize that plasma.

The experiment is limited by its size and by budgets and so on. So we’ll be looking to scale that up. But the physics, in some ways, will get even easier as we get to a larger scale. We have this linear device, we’ll be able to scale by adding in extra modules. That will give us an ability to have modular construction, making the same components time and time and again, so we can come down the cost curve on those.

So the next project will be a larger demonstrator?

So the next step for us will be to build a larger, simple mirror, and that’s something that we refer to as Anvil, but that will be located in our purpose-built R&D facility called Realta’s Forge. And then ultimately we get to a tandem mirror. That’s what we call Hammir.

We have the WHAM experiment operating right now. We aim to have Anvil operating within this decade, definitely by 2029, and we aim to have Hammir, the first energy producing plant, online in the mid-2030s.

How are you thinking about the market for this concept down the road? Where do you expect initial customer interest to come from?

Fusion is still a long timeline by startup standards, compared to software or whatever else. One of the key things we want to do at this stage is make sure we have a broad set of options, and we keep those options as open as possible, because we’ll see what happens in the coming years. Would it be that to continue operating data centers, big tech, in order to maintain a social license, absolutely needs to do zero carbon energy, and they need a firm, always-on solution to go hand in hand with intermittent renewables? That’s one opportunity.

You can look at heavy industry, things like petrochemicals, where a large part of their carbon footprint is the natural gas or other fuel that’s burned in the manufacturing process, to provide process heat. We may go after those as well. And process heat is a huge and varied market.

You’ve got aspects like the military here in the US which are looking at security of supply to power bases, particularly remote bases, being having to rail in or truck in fuel, is a major weak point for our security. Being able to have a firm, always-on energy source on base that requires a very, very small amount of fuel to keep ticking along for years is something that they’re interested in as well.

On the supply chain side, are you expecting bottlenecks or limitations in your ability to get the components you need? Where are those areas of need?

I was actually asked to speak at a conference on this last year, and everyone that came in expected me to talk about magnets and superconducting tape and so on, but I focused the entire talk on people. That’s one of the biggest constraints that doesn’t always get the attention that it needs, is that we need lots of scientists and engineers to work on this.

Fusion research was in the doldrums a bit for a few decades. Nuclear engineering, definitely, for my generation, was not an attractive path for people going to university in the late 80s, 90s and so on. But that’s come back around. There’s definitely more and more students interested in alternative energy, interested in nuclear writ large, and interested in fusion. But it’s still not enough. We’re going to need an awful lot of people, and it’s not just PhD physicists or electrical and mechanical engineers and so on. We’re also going to need high voltage electricians, skilled machinists and welders.

High temperature superconducting material for magnets, and then the magnets themselves, are things that people tend to focus on, but I get the impression that that’s going to be a solved problem. There are enough companies lining up to make the tape, and then there’s plenty of companies out there who are looking at making the magnets and so on as well. There are companies looking at things like the tritium loop that needs to be kind of peripheral around the fusion power plant. So those are all happening.

We’ve made a decision at Realta that we are not going to do everything ourselves. There’s often a fetish in Silicon Valley about startups being vertically integrated, building everything themselves, because it gives you kind of control over your own destiny. Yes, but that comes at a cost and a level of complexity, and we think in fusion we are better at working with external partners on a number of those subsystems and peripheral components to make sure that we have the best chance of being successful in a time frame that’s still going to make sense for the world.

Any thoughts you want to leave us with?

Energy is what underpins civilization. I don’t think it gets as much attention from the broader public as it deserves. We are going to need all of the solutions. We are definitely in a race to tackle climate change, but even beyond that, we need energy if we’re going to power our economy, and we’re definitely tackling that. We see fusion playing a significant role, and we are getting us to a world where we can switch from having a scarcity mindset on energy, where it’s all down to which countries have the oil and gas or who’s got access to it, and instead get it to a point where, hey, we’ve got the technology, and we can essentially make energy. Physicists will jump up and down when I say that.

We need an all-of-the-above solution.

Lead Reporter of Ignition