In the world of deep tech venture capital, a16z has become a force. The firm made a name for itself with pragmatic investments in companies looking to scale transformative tech benefitting the national interest—and they tend to be boundary-pushing industry leaders in their fields.

David Ulevitch and Katherine Boyle started the American Dynamism practice two years ago to find companies with the potential to significantly support the US interest. The practice spans aerospace, logistics, manufacturing, and industrials—anything made of nuts and bolts that impacts US national security. To date, American Dynamism’s investment in nuclear consists of the microreactor startup Radiant.

Ulevitch is bullish on the future of the nuclear fission industry and its potential to ensure energy security and independence at home. Ignition sat down with him to hear where he stands on the nuclear sector and its potential for returns and adoption.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ignition: First off, tell me a little bit about your personal goals when you’re investing through American Dynamism, and how that relates to the energy sector.

With American Dynamism, there’s an opportunity to invest in the cornerstones that underpin the American economy and our allies’ economies. And oftentimes that involves touching things that have physical components, that tie into energy, that tie into space, that tie into defense. The ultimate goal is to have big venture returns, big outcomes, as well as having a big impact. American Dynamism sits right at the intersection of those two things.

Most of the companies we invest in are still traditional software companies. They often have a hardware component. But because so many of these companies, especially whether they’re in the AI space or the defense space, require energy—there is no defense without energy, there is no AI revolution without energy—energy is just a fundamental component of our investing thesis. We have an insatiable thirst for energy, and people want clean energy, and so we have a small part of the practice focused on how we can make sure that we can power our way forward in the next 100+ years.

I feel like it’s only been recently that I’ve really been hearing nuclear energy companies talk about the military applications. People talk about the climate impact, people talk about resilience. But I’m curious what got you to draw that connection between nuclear energy and the DoD military application?

First, I think people have to remember that the US Navy has built and deployed more nuclear reactors than anywhere on the planet in the last 50 years. They’re not AP1000s that are powering cities like we have in Georgia now, but they are building new nuclear reactors and putting them in vehicle vessels and using them, whether they’re submarines or aircraft carriers. And so they have a ton of experience with nuclear, and they understand the need for energy and energy management more than anyone else. The US military, just as a whole, spends an inordinate amount of money, time, people, and logistics effort just to move fuel around. If you think about how we move fuel around the world to satisfy our forward operating bases and our military endeavors, it’s a massive expense, and it puts lives at risk. I wrote an essay recently about energy and defense, and if you can remove the need to constantly have these fuel resupply lines like we had in Afghanistan and in Iraq, you will save lives, because that’s when soldiers are put at most risk.

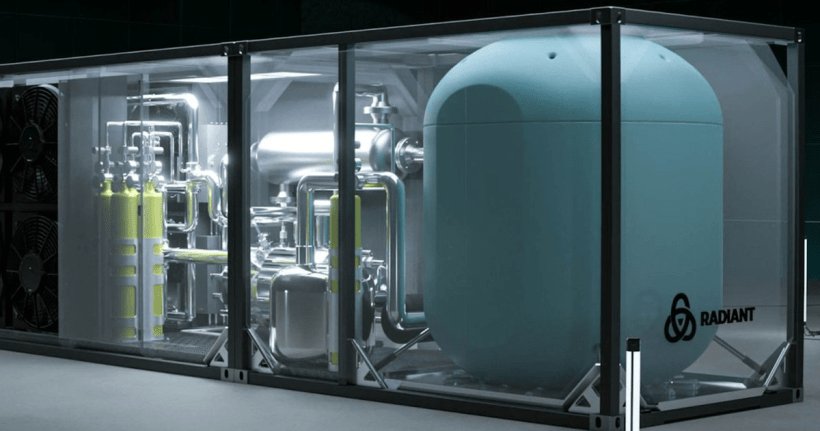

We also have the ability to then deploy resources more quickly. Nuclear is a way to deploy energy quickly. It’s baseload energy. It doesn’t require the sun to be out or the wind to be blowing. It’s clean energy. From an energy impact standpoint, you can have a small amount of nuclear power generating capacity and a small footprint and generate a tremendous amount of electrical capacity. We’ve talked about Radiant Nuclear before, but in one shipping container, you can generate a megawatt of energy. And that’s just really, really powerful.

That shippability and ability to rapidly deploy sound like key areas when you’re investing in the space, and Radiant ticked those boxes. How do you think that the companies in the space operating right now are doing when thinking about meeting the DoD needs in those areas?

There’s a number of companies building what I would call SMRs, but Radiant is the only one that’s really building a modular microreactor. And by modular, I mean that there will be a factory that is producing these reactors and then shipping them in planes or on 18-wheelers or on trains. People lump them into a similar category of microreactor or SMR, but really, the modular microreactor that Radiant has is really in a class of its own, and that fulfills a generator replacement need for a forward operating base.

I do think the DoD is totally attuned to it. I think that our government has realized that energy is the fuel, quite literally, that allows us to survive and operate. It’s not just the DoD. The whole federal government has had a renewed interest in nuclear because they recognize, if we want to have a clean energy transition, there’s two dimensions to this. One is they want to have a clean energy transition. But the second is that we just need more energy generally, we just have this insatiable thirst for energy.

Nuclear has gone through this series of development cycles. You could call them hype cycles. And we’re in the midst of a resurgence now, seeing increased investment and enthusiasm for climate and for resilience. Do you think that this is the time that it sticks?

Yeah, I think a number of things have happened. First, I think that people realize that the lies that were told by the Sierra Club over decades have just not been true. Nuclear waste is not a major problem. I understand that people don’t like the idea of nuclear waste in their backyard, but nobody’s going to have nuclear waste in their backyard. From a safety standpoint, nobody in the United States has died from a nuclear power related incident. To my knowledge, I think that number is still zero.

There were a lot of lies that people had to realize were not true. They sounded good on paper, they sounded good conceptually, but in actuality, and that’s all that matters, none of them were true. Nuclear material is safe. Storing and disposing of the waste is safe. We don’t have to strip mine the earth like we do for coal. We don’t have to frack across all these different states to try to get natural gas. It’s just much, much easier, and it’s super resilient, reliable and modular.

We’ve also made advances in construction techniques. So we now know that there are plans that are by default safe—that are meltdown proof, that are only on when they’re active and default to being off. We can build much safer nuclear power plants, and so we should be. I think people realize that, and I think it’s a bipartisan issue.

While we do have more advanced construction capabilities now, there’s also been a decrease in the amount of people in the US who know how to build these kinds of things, and people are worried about that as kind of an existential problem for the nuclear sector. Do you think that advanced reactor technologies address that problem by utilizing more advanced construction techniques, and how do you think about the issues on the labor side?

One of the things we saw with the Vogtle reactor in Georgia, and one of the reasons why it was a decade late and $10 or $15B over budget, is that they had to go find a new workforce—and not just the workforce to build it, but even all the subcontractors that make all the materials and the concrete casting and all the things that go into making it, even before it even gets to the site and gets assembled and put together. There was so much work that had to be done from an entire workforce that had not been hired or trained or built a nuclear power plant before.

They actually saved a lot of time when they went from Vogtle 3 to Vogtle 4. And the greatest catastrophe in nuclear power in the last 10 years is actually not having Vogel five, six, seven, eight, nine, 10 all lined up to go, and just taking that workforce that knows how to do this and moving them to the next project. That, to me, is where the government has a major failing. We can find the capital, we can find the site selections, but it’s like, “Okay, we have this great workforce that just built this AP1000, they should just be going from site to site and building them.”

To answer your question about advanced design and techniques, look—companies like Radiant and others are now developing new reactor designs that are much simpler. They’re much more straightforward, they leverage our better understanding of physics and nuclear physics. I think that enthusiasm will create an opportunity for more people to want to build reactors. And Radiant is unique in that they’re building a factory to build reactors, so all the knowledge will be in that factory, as opposed to having to go find and hire new people at a new site in a new state every time. They’ll just build the reactor at the factory and then ship the reactor to wherever it needs to go.

What do you think about the issues in the supply chain for nuclear power, considering issues now with getting HALEU fuel and potential issues earlier on in the supply chain? Do you have any concerns about the vulnerabilities there when it comes to supplying the military?

Look, the best way to solve a supply chain issue is to have a crisis. America is the best in a crisis. We are not always our best when we don’t have a wartime mentality. And I don’t mean wartime as in we’re actually at war, I just mean when we have a reason to move with a sense of urgency and a sense of purpose and cut through red tape and cut through a bunch of baloney. That’s what America does best. We saw this during COVID when it came to the vaccines compared to the rest of the world. We don’t have a crisis right now, and so it’s hard to fix the calcification of the supply chain.

Separate from the nuclear fuel you would need, like the TRISO fuel or the HALEU to make the TRISO fuel that you would need for something like Radiant or some of the other new SMR reactors, or all the reactors in the Pele program, but even radioisotopes that we use in the medical industry. We’re just going to run out of those radioisotopes. We bought a bunch from Russia in the ‘70s and we don’t really make them here in the US anymore. And these are critical isotopes, from scientific detection capabilities to medical imaging. We could make more of these radioisotopes with non-electrical reactors, but we don’t really do that.

Really what you need is government leadership to say, “Hey, this is actually a priority. We’re going to commit. If you build it, we will buy it.” That’s where we’re missing today. The government has a role to say if you build it, we will buy it.

A theme of American Dynamism is our work with the government and the supply chain resources. We certainly have the knowledge. We have the raw materials. We can go and enrich uranium. We can do all these things. We can build the reactors to generate radioisotopes. We can do all these things. We just aren’t.

Where do you think that the US government should be applying more influence and maybe allocating more funding for the growth and sustainability of the sector?

I don’t think it’s funding that’s actually the gap. I think that it’s legislation to compel the NRC to grant nuclear licenses. I think Congress can pass legislation, and then certainly the executive branch can pass executive orders that compel the NRC to approve new modular nuclear designs, new SMR reactors, and guarantee their approval for nuclear fuel. We have created an NRC that is better off not approving anything, because then they never get in trouble, when really what you want to do is say that you will get in trouble if you don’t approve things.

And you want to simplify the regulatory environment. That is one area where AI, I think, will play a role. The nuclear regulatory environment is so complicated that this is a place where AI will do a much better job of simplifying

Besides the actual power generation piece of the nuclear energy sector, are there any other areas that you’re interested in from an investment standpoint?

I do think the radio isotope market is a critical market, whether it’s a venture scale market for us to invest in, I’m not sure, but it’s important to the national security of the United States. There’s a lot that I know are critical to both healthcare diagnostics and useful in scientific research, and if we don’t have them, we either can’t do scientific research or you can’t provide people the best healthcare possible. And so I think that’s a huge area. I would say I’m loosely interested, but not an expert.

Besides Radiant, are you looking at any other potential investment targets in the nuclear energy production space?

We’ve looked at a number, and we might make more investments. The one nice thing about nuclear power is that if you’re building a 100 MW nuclear reactor, you’re not going to compete with somebody building a three MW nuclear reactor. It’s just totally different markets, totally different use cases. One might be used for helping you get to that sort of gigascale data center, and one’s going to be used for a forward operating base. I think you can make multiple investments in the nuclear space without having any conflict. We certainly are open to that, and we look all the time.

We’ve been talking about the fission sector in this conversation, and that’s where a16z has invested to date. Do you think at all about fusion as a venture scale business right now, or is it too early?

I know smart people are certainly putting money that way. I’m an LP in funds that have made fusion investments. We haven’t made one. There have been different moments in time where we’ve tried to go deep in understanding where we are—are we 10 years away from a commercial fusion reactor? Are we 20 years away? I don’t know that answer, and I tend to avoid things that are sort of scientifically still unproven. Despite the advancements in fusion, in the sense that people have that it’s an inevitability, I’m not quite there yet. So we have not made them.

Lead Reporter of Ignition